“Go and get the cones to help the boys. One hand washes the other and both hands wash the face.”

This is the first of many shouts that Mr. Ozias Mattos gives at the beginning of a training session. On Friday morning, he’s in charge of a few boys practicing offensive plays under a hot sun in Osasco, in the São Paulo region.

The team’s right-back suffers. The ball bobbles on the pitch, which has sand down the wings to avoid the mud, making a first-time cross almost impossible. “When the ball comes like this, you control it first, then you cross,” shouts the coach, who was a Palmeiras player in the 80s.

There is absolutely no luxury whatsoever at the Champions Ebenézer Football Club. In a humble ground loaned by the city, the intention is simple: to teach boys to play football and try to direct them to a professional career.

Most of them can’t achieve it. Some end up getting places in small Brazilian sides, or are sent to distant leagues in Mexico or Qatar. Few make their way to a big club. And one, only one, has on the front or back cover of European newspapers this week.

Ederson has just been sold to Manchester City, a club whose dimension is far from Champions Ebenézer’s reality. But 15 years ago, that’s where Manchester City’s new star was, training on the dirt pitch under a scorching sun.

“His father came to my house and clapped,” says the coach, who was Ederson’s neighbour. “He said: ‘Ozias, I would like you to train my two children’. I said: ‘Okay, I’ll take him and I’ll train him’. But as I trained the elders, I said ‘Giba, start training him’.

“He was nine when he arrived here,” Gilberto Lopes, known as Giba, tells me. “He was not even a goalkeeper. He was a fullback. I put him there because he was left-footed. But he didn’t show much. He did hit the ball well, but it was kind of ungainly.

“Then one day I put him in goal. He did well. I said, ‘Look, you’re going to stay in goal because you have quality.’ That was about two, three months after he arrived.

“At first, he didn’t like it very much. But then he got the taste. Then he told his mother: ‘Mum, I want to stay in goal’. That’s when I said: ‘Nice. Even better. In the goal he’s more resourceful’.

However, Ederson’s quality was too much for the small club. Taking care of everything by themselves, Ozias and Giba never had the money to pay a goalkeeping coach. At first, the balls and vests were bought with donations from parents, who would give around five reais (£1.50) to make the whole project possible.

That’s why when he was still ten, Ederson was sent to a big club. Thanks to the friendships that Ozias and Giba have in the clubs of São Paulo, it was easy to send him to train in a better structure.

“He was evolving, evolving, then I called Toninho Natal, from São Paulo. Ederson was 10 years old. It was three months later. I called, and Toninho said: bring him. I brought him, and in the first practice, Toninho approved him. Then he spent six years at São Paulo. He already had talent. He was born with it. He only needed a little work, sorting out a few problems, but he was practically complete.

“But there was a director there who never really liked us. He used to give more priority to other agents. We are not agents, we discover and form. The boy was getting better and better. Then São Paulo suddenly released him.

“He was sent to play for Cruzeiro, he was going to live in the training centre. But this situation arose. Toninho Natal, who approved him, when he was fired, was approached by an agent who works for Jorge Mendes called Ênio. He spoke of this goalkeeper and said he should take him, with no fear.

“Ênio spoke to his father, his father sent him to us. We talked to his father and we came to an agreement that he would go to Benfica, because Benfica was better (than Cruzeiro)”.

“They (Benfica) said: ‘But we want to see a training session.’ Ênio asked me: ‘He won’t embarrass me, will he, Giba?’ I said, ‘No, relax.’ My partner came, kicked some balls. Ederson made four saves and that was that. He left. And today he is what he is. One of the most expensive goalkeepers in history.”

Expensive but not always rich. Giba says that Ederson’s childhood was not financially easy, and that it was the great mentality of his parents that helped him get so far.

“This boy lived in a free area. The situation of the parents was very difficult. He comes from a very poor family, but a psychologically structured family. Parents who are present. They are people who have good nature. They teach their son what’s best.

“This boy lived in a free area. The situation of the parents was very difficult. He comes from a very poor family, but a psychologically structured family. Parents who are present. They are people who have good nature. They teach their son what’s best.

“Because here is a complement of the home. Our boys do not say dirty words. We do not let one boy disrespect the others. There are boys from Alphaville, but there are boys from the favela.”

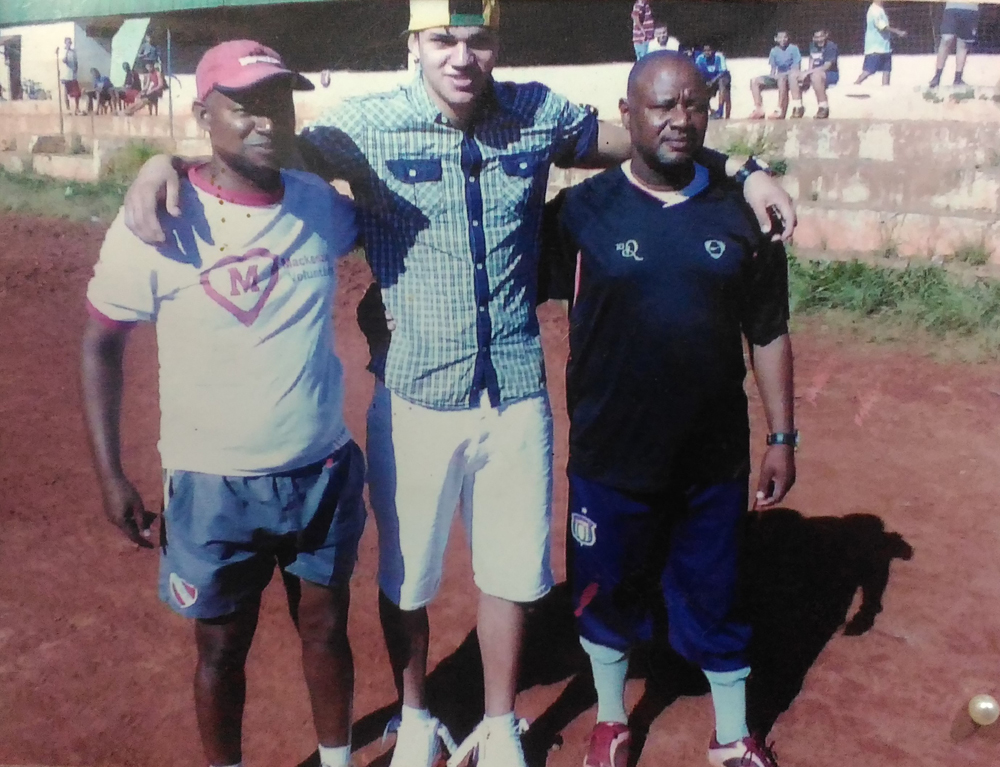

Ederson’s career and move to Manchester City may be something that makes Giba proud, but this is not the only reason. The goalkeeper is one of the few who still recognises the work of his former coaches, and is grateful enough to return to the club and visit them all.

“He’s a good-natured boy, an educated boy. Called for the under-23 national team, champion for Benfica, and still comes to play barefooted here on the court.”

“He comes here,” confirms Ozias. “It’s humility. One day I was training the boys, it was raining, he came down here and started training with me. I said ‘damn’. The boys were all surprised. I said, ‘Relax, he started just like you are now’. He started slapping the boys’ heads and training with me. You see the humility. There are guys who don’t even come here.”

But of the €40m paid by Manchester City to Benfica, not a penny goes to the Champions Ebenézer. Because it does not have a structure of its own, it’s not always possible to do the documentation of the youngsters, and in the case of Ederson, the player left too early.

“Nothing, nothing,” says Giba. “São Paulo will win I think €1.7m in the transaction, if I’m not mistaken. And São Paulo sent him away! Although São Paulo developed him, whether we like it or not, they had the structure, everything, so he could reach a certain level. But São Paulo will get this money, everyone will win, I will not win anything. I will win as soon as he speaks like this: take Giba here, to help you.”

This is a frequent problem at the club. Besides not getting the transfer fees, the ex-players don’t help either.

“They (the city) were even paying us a salary, we were hired and everything. But since January I do not get a penny. The mayor was changed, and this mayor is having this problem and can’t hire anyone.

“It’s a struggle here. It’s very hard. We unveil the player and have no structure to keep him. For Wellington (São Paulo midfielder), I did everything. He slept at my home, he ate at my home, he was from the East Zone, he did not have much of a condition. Sometimes I paid a ticket. Today the boy earns R$300k (£71.6k) and does not give me a penny.

“After 13 years, he came here. He said, ‘I’ll help, Giba.’ I said ‘nice’. I made a budget to do something on my teeth, I had an eye problem, and I talked to him. He gave me that shirt and gave me two thousand. I said: ‘But it will cost more than 20 thousand’. He said: ‘No, but I can only give you this’. I still took 500 and gave it to my partner because he needed it. I could only put new glasses on. Even lost the eye. He did not help.”

That’s why the affection for Ederson is something different there. The coach has full confidence that because of the strong relationship he still has with the local people, he will be one of the few who will give some financial return to the club: “I believe so. He is a boy who recognises it. I talk to him once in a while, he says: ‘you can relax Giba. I will not forget you and Ozias.

“He’s grateful. He speaks and I believe in him, in the father, in the mother, Mr. Bartolomeu, Dona Joelma, I believe. Without hesitation, he will help our work here. Now the others, I don’t believe them.

“I was very happy (for the transfer). He left here, it will magnify our work and everything. But no one lives from status. The bills keep coming.”